The N.I.C.U. Queen

We chose our OB-GYN for two reasons. One, we were misled into believing we could switch HMO medical groups after Candy was pregnant to get a doctor we wanted. Turns out not so much: pregnancy is a pre-existing condition so we had to stay with the doctor in our medical group. It is possible to get around this with a permission letter from your new medical group saying they accept the new patient despite their obvious flaws, but this was obviously going to be a huge pain in the ass. We decided against exploring this option as Two: our OB-GYN would deliver us at Providence St. Joseph Medical Center, which has arguably one of the best Neonatal Intensive Care Units (NICU) in all of Southern California.

With modern technology doctors can deliver babies that will survive as early as 22-24 weeks. This is just over 5 months. These pound and a half babies are a mess, with nothing properly developed yet, from skin to heart to lungs to eyes to liver, etc. Going into this we hoped we would not need to deliver that early and would therefore not need this great NICU. We felt very fortunate to make it all the way to 36 weeks before our babies were delivered, placing us right around the median delivery age for twins. Twins still tend to be born a bit small, but 3-4 weeks earlier than the traditional “singleton” baby is just fine in most cases. So we assumed we were in the clear. Well, you know what they say about what “assume” makes of you and me…

The hospital has no middle ground between babies being allowed upstairs to be with their mothers and the NICU. So when they finally determined that “Baby B” was not going to be able to rapidly clear her lungs, they reserved a cradle for her in the NICU, Bed 11 to be exact. Dazed and Confused (my new ring tone by the way), her mother and I settled down in our tiny hospital room complete with fold out husband-bed, dealing with our brand new baby as best we could and hoping for better news in the morning.

The NICU is a secure, sterile space. To enter you hit a button outside two imposing doors and then stare into a HAL-9000 looking security eye. Someone might answer right away, or you may have to hit the button repeatedly. Eventually you state your name and that you are a parent of a NICU baby and they unlock the door. This gets you into the foyer where there is a check-in desk and a hand-washing station. This is where you need to scrub your hands up to the elbow for a full three minutes, like you were a doctor about to go into surgery. The first time you do it you feel as though your hands have never been cleaner. By the 20th time you feel a bit like an overworked dish washer.

The main room of the NICU is row upon row of baby incubators, plastic boxes with little doors on the side, as if instead of babies one were handling toxic or radioactive materials. Every incubator is hooked up to a series of monitors. Every baby has its heart, temperature, oxygen, and respiratory rate monitored. Alarms are a regular occurance in the NICU, with one going off somewhere every 5-10 minutes. The majority are reading errors or tiny temporary spikes, but the nurses are always running this way and that, punching buttons, adjusting monitor leads, and calling for help. Despite all that there is a definitely sense of tranquility. These babies are quite sick and weak and most are likely to stay that way for a long time, so you can’t sustain a sense of desperate urgency.

The NICU is set up in rows of three, with about 18 total beds, nearly all filled. Our baby is in the middle incubator in one of these rows. On either side of her are seriously premature babies, little 1-2 pounders, so undeveloped and so small they don’t really look like babies at all but some other poor, sick mammal. Each has so many machines hooked up to it you can hardly see the child. Air oscillators pumping air into their lungs, blood transfusing, intravenous drugs pumped into their hands, bright UV lights helping their livers break down their body waste products. These really tiny babies basically have their own 1-on-1 nurse assigned to them, showing how constant monitoring is required to keep them alive.

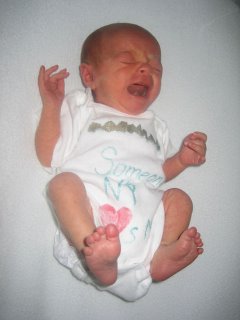

Our daughter was born at 5 pounds, 6 ounces, truly a giant among this teeny, tiny population. While initially given an IV and some oxygen, in just a day or two she has both those removed, leaving only a NG (nasogastric) tube for putting food directly into her stomach through her nose. This is required as her breathing rate is much too high for normal feeding, spiking as high as 140 breaths a minute, a hyperventilating pant that she is doing to counter the decreased oxygen she is receiving because of the fluid in her lungs. Watching her, you can see her breathing ease and slow, then something catches (assumedly the fluid) and the breathing rate skyrockets again. Even so, she is clearly in a whole different class of health than her surrounding incubator-mates. A real Queen of the NICU.

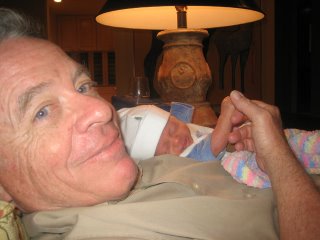

Candy first got to see her second born (by a minute) in the late afternoon of the next day. Still literally stapled together, she had to be wheeled down to the NICU and propped up to wash her hands. She would be able to leave the hospital in 3 more days. Kayla, who we were finally able to name once Candy had seen her, would be there almost 2 weeks.

The hardest part of visiting Kayla in the NICU was definitely leaving her. Especially if you arrived before feeding so you were allowed to hold her for a while. Putting your child back in the plastic cube to have fluid pumped into her stomach… that is tough. Throw in some exhaustion and sleep deprivation and it was not hard to tear up a little bit. Sometimes I had to literally flee the ward to keep myself together.

The second hardest part was getting realistic information out of the NICU staff. The nurses are completely geared to ease fears and settle nerves, so they always had very encouraging but highly vague tidbits to give out. -- She is a little better. She was good last night. She should not be here too long. -- This is not entirely their fault, as the final say on child health really belongs to the doctors. If a nurse says something to get a parents hopes up or makes them upset and it turns out to be different than what the doctor would say… well, they would get a lot of crap. NICU babies appear to not be assigned a particular doctor, necessarily, but are assigned to the staff. This makes it more difficult to find the person who can really answer your question. Particularly the critical question: Realisitically, how long will my child be here? If I had one complaint with our stay at St. Joe’s, it would be that there should be some more systematic way to get information on our NICU children without having to ask whatever random nurse is on duty. It really led to a lot of unnecessary frustration with an already difficult situation.

After seven days Kayla’s breathing finally cleared. Candy, Rylie, and I had been home for 3 days at that point getting the nursery prepped and adjusting our lives to fit this new significant responsibility. It was sort of like we had a starter baby, to get ourselves adjusted to this new crazy parent-thing. Except that we had to go to the hospital every day, usually carting along our tiny little companion.

We wanted to take Kayla home right then, but what we had not been told before was that even when her breathing cleared, it would take days to wean her off her stomach feeding tube. Until it could be demonstrated that she could gain weight from regular feeding they would not release her. It was at this point I became very frustrated and bitched incessantly to anyone foolish enough to engage me on the subject. I am sure my increased irritability from lack of sleep did not help.

To complicate matters further, Kayla took to breast feeding right away, but had some initial trouble with the bottle. As we wanted to get her home as soon as possible, this meant we had to try and be at every non-lavage (lavage is medi-speak for stomach tube) feeding. At first this was not so bad when the non-lavage was only once a day. However she did very well and it ramped up quickly, so we soon found ourselves traveling to the hospital over and over at all times of night, including a mildly scary midnight feeding where we had to enter the hospital through the emergency room and travel through the whole empty hospital. Have you seen a hospital-based horror movie? Yeah, it was like that.

Finally we managed an all day hospital stay where they gave us a special room, so we didn’t have to go back and forth from our home. Rylie and Kayla met for the first time since their birth ten days before. This was an astounding success and Kayla finally got her nose tube out and was sent home on Sunday, October 29, at the tender age of 11 days. We could finally celebrate, which we did with a nice Belgian lambic. Of course, now the work has really begun.

This ends this little series, but I assure you there will be much more of these little rascals to come…